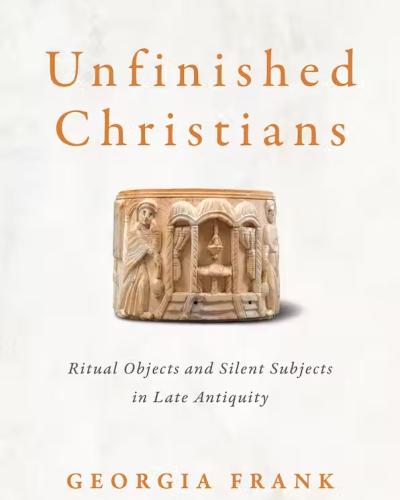

This iteration of the Fellows’ Q&A series features Georgia Frank, Charles A. Dana Professor of Religion at Colgate University and 2020-21 “Fabrication” Society Fellow. Her new book, Unfinished Christians: Ritual Objects and Silent Subjects in Late Antiquity was released in February 2023 from University of Pennsylvania Press.

Big Picture

My book, Unfinished Christians: Ritual Objects and Silent Subjects in Late Antiquity, explores what we can know about the lived religion of ordinary, non-elite Christians in cities during the fourth through sixth centuries. These three centuries reshaped the religious lives for Christians. The lives of extraordinary Christians have been the subject of important studies. Late antiquity, which includes the legalization of Christianity in the early fourth century and the centuries prior to the Muslim conquests of these regions in the early seventh century, was a time of religious experimentation and innovation. Christians wrote biographies of miracle-working saints, went on pilgrimages to the newly built sites associated with events from the Bible in the emerging Holy Land, and shared stories about ascetical monks and nuns who lived in solitude and formed communities in the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. The rise of pilgrimage, church-building, healing centers, and veneration of relics have also left an abundance of material evidence related to the rituals of Christians. How ordinary Christians felt and experienced these rituals has been less well understood, however. This book attempts to fill that gap by asking what historians of religion learn about laity from the writings by educated elites. Its chapters focus on baptismal instructions, ancient workshops, processions, mixed emotions experienced during sermons, and the interplay of emotions and senses in all-night vigils. These sermons and songs provide sources for the ritual lives of now anonymous ordinary Christians in urban centers such as Constantinople (Istanbul today), as well as Antioch in and Cappadocia (in southcentral and central Turkey today).

The stakes are considerable. How shall historians access lives of non-monastic, non-ordained, non-aristocratic Christians, if almost nothing written by them survives today? Shall the ritual lives of ordinary Christians remain consigned to oblivion in the near absence of written sources by them? I argue that even when the written record of elite, clergy, and monastics is far more abundant, historians may study these writings for evidence of the bodies, feelings, and senses in their midst. I trace how these written sources were performative in their original setting. Drawing on theories of lived religion in contemporary religion as well as in antiquity, I provide ways of reconstructing performative and ritual settings for sermons delivered in the presence of lay audiences. The book considers the embodied experience of ritual instructions received when preparing for weeks and even months for the culminating conversion rite of baptism. I also considered how ritual handbooks written by and for clergy may provide clues to the mixed emotions that biblical readings and prayer/psalm verses elicited during specific biblical commemorations over cycle of the Christian liturgical year. The final chapter considers how rhetorical practices immersed audiences into the interior lives of bystanders in biblical stories.

In Particular

Archaeologists and art historians have done tremendous work on the buildings, fixtures, and decorations of ancient Christian baptismal spaces, which were often annexed to churches. Building on their work, I focus on other types of spaces that adults preparing for initiation learned to imagine. Specifically, I focus on the importance of workshops and other fabrication spaces for baptismal instructions. To be sure, water metaphors figured prominently in preparing candidates for water rituals at the heart of baptism. Catechumens, as they these candidates were called (from the Greek word echo, or hearing), learned stories from the Bible about the rivers in the Garden of Eden, the flood that Noah’s family survived, and the parting of the waters when the Israelites fled slavery in Egypt.

Preachers relied on the language of workshop, fabrication, and apprenticeship to underscore the personal effort, patience, and training needed to become Christian.

Even so, there is also an abundance of metaphors drawn from craft and artisanry in baptismal instructions. Preachers likened baptismal initiation to a workshop. They compared baptism to how it might feel to be smelted, fired, dyed, carved, melted, molded, painted, drawn, or chiseled by many hands. Such material metaphors captured the iterative and cooperative processes required to become Christians and the vigilance needed to avoid damage or mend disrepair . Preachers relied on the language of workshop, fabrication, and apprenticeship to underscore the personal effort, patience, and training needed to become Christian. Recent studies about the archaeology and organization of workshops in antiquity allowed me to understand these metaphors had on religious self-understanding. More so than water, the workshop in antiquity—a familiar site in urban centers—conveyed the structured cooperation, iterative processes, mistakes, and repairs required to become a new object. Candidates preparing for baptism learned to think of themselves simultaneously as apprentice, craftsperson, and object of their emerging religious identity.

Discovery

What surprised me is how a project about the history of the emotions evolved into a book about spaces, the senses, and mixed emotions in early Christian experience. What inspired me was having such remarkable access to choreographers, textile historians, political theorists, poets, and musicians as conversation partners. As I think back to all the discussions, insights, new books, and rich talks I experienced during that strange covid year, I look back on how much these encounters gradually shifted my perspective. I marvel at the access I had that year to every scholarly resource imaginable on workshops in antiquity. Thanks to swift and contactless library services, I benefited from conference publications about labor and workshops in antiquity, archaeological field reports including volumes on fabrication quarters in Byzantine Sardis (an archaeological excavation in Turkey co-sponsored by Cornell), the use of geophysical surveys to detect factories on the outskirts of ancient Ephesus, what detritus from ancient workshops (unfinished heads, seconds, and practice pieces for apprentices) revealed about collaborative maker spaces, and a papyrus containing a contract for a young girl apprenticing with a local weaver. Serendipity and necessity became the mothers of invention during the final year of the book project in a remarkable place resonating with the melodies of the Cornell chimes.

Serendipity and necessity became the mothers of invention during the final year of the book project in a remarkable place resonating with the melodies of the Cornell chimes.

Fellowship

“Fabrication,” our theme for that year, guided my investigations into new regions, time periods, disciplines, and theorists I had not anticipated when I had applied for this fellowship. In our weekly seminars and over lunch afterwards, Fabrication fellows listened patiently as I asked rather naive questions. Their generosity emboldened me to explore new methods. They introduced me to valuable work by theorists intent on recovering silenced bodies and voices from historical records (archives) that never fully controlled, silenced or erased the people in their records. In particular, the work of Saidiya Hartman on the legacy of slavery and recent work on of enslaved labor in antiquity equipped me to reimagine the audiences for early Christian preaching and singing. With a variety of zoom conferences and lecture series just a click away and contactless access to a remarkable library collections, I could now dive more deeply into new questions about urban life in late antiquity. The audiences for the zoom presentations I delivered to my home departments—Classics and Near Eastern Studies—welcomed my work and pushed me to refine ideas. As the snows receded more socially distanced walks through gorges and gardens provided some of the richest conversations I had had about the project. The students in my SHUM seminar on the emotions in antiquity opened my eyes to new ways to study the role of the emotions and the imagination in storytelling, worship, and material cultures of antiquity. Without the ingenuity of SHUM’s interim director, Annette Richards, and the remarkable staff who kept us safe and connected throughout the pandemic, this project about the “unfinished” would have surely remained unfinished. I am indebted to my entire cohort and colleagues at Cornell for this remarkable opportunity.