Speakers

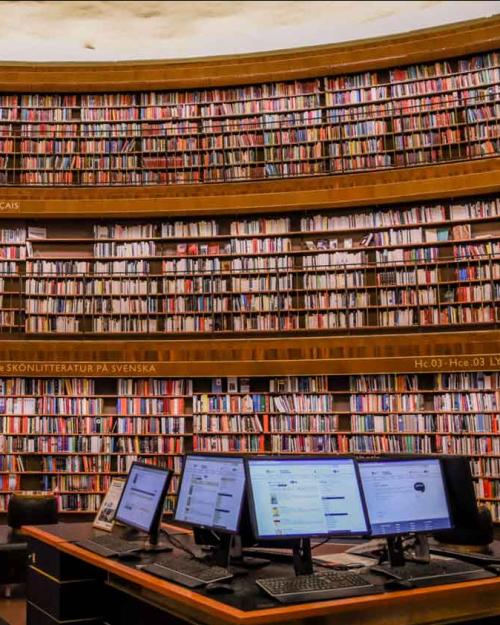

Annette Richards, interim director of the , professor of music, and Given Foundation Professor in the Humanities, Cornell University

Adin Lears, 2020-21 Society Fellow and assistant professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University

Anthony Lovenheim-Irwin, 2020-21 Society Fellow and scholar of Asian religions

Transcript

Annette (00:05):

Hello, and welcome to the Humanities Pod. I'm Annette Richards. And we're talking today about craft and creation, creatures and construction. It's all about the ethics and poetics of fabrication, which is the theme for this year at the .

Music (00:22)

My two guests today are Anthony Lovenheim Irwin and Adin Lears, both Fellows at the this year. Anthony is a scholar of Asian religions whose work focuses on the intersection of religion and craft, especially on handcraft and construction in Thai Buddhism. His project this year is titled “Building Buddhism in Chiang Rai, Thailand: Construction as Religion.” Adin is assistant professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University, and she works on sensation, affect, embodiment, and language in medieval culture. Her book, World of Echo: Noise and Knowing in Late Medieval England came out in 2020 from Cornell University Press. And her current project has the working title “Little Science: Craft Knowledge and Creature Futures in the Age of Chaucer.” It's great to have you both here. Welcome to the Pod.

Music (1:20)

Annette (1:26):

So let’s start with what's on your desk, or perhaps on the desktop of your mind right now— with your own individual scholarly projects. Give us a sense of what it is you're doing, of the central themes you're grappling with, the big question at the heart of the project. Why don't we start with you Adin, and then we'll go to you Anthony, and feel free to jump in at any point.

Adin (01:52):

Sure. Thank you. So what I'm really trying to do in its broadest sense with this project is think about how medieval thinkers can help us reconfigure our relationships to other people and to our environment and to objects and technologies within it. And I want to think about how medieval texts help us forge more just social and environmental ecologies, moving away from a kind of instrumental relationship toward a kind of hospitality and accommodation of difference. This project began as a project on craft and making in medieval literature, the ethics of craft and making, and the ways that medieval thinkers considered actual fabrication as a type of self-fabrication as well, an ethical self-fabrication, and even a kind of soul work perhaps.

I've recently taken a turn to become really focused on the idea of “the creature” in the middle ages; particularly in late medieval England. In Middle English, the term had a connotation of being a created thing. So it has this sort of object-ness or object-hood associated with it as well as a kind of animacy. And I'm really interested in the ways that it positions the human as an object or an animate thing that has a kind of materiality and fleshliness to it as well. And I have a sense that this can help us think about these ways of reconfiguring relationships between humans and other creatures.

Annette (03:43):

So let’s turn to you Anthony, and ask the same question about the central focus of your work this year.

Anthony (03:49):

Thank you so much, Annette and Adin. The big thing that I'm working on, it's the second part of the title of my project “Construction as Religion.” So it's approaching religion through the act of crafting, building, construction, renovation, basically material and spatial production. And it comes out of a religious studies tradition of working on what we call “lived religion,” which means not just looking at the texts for answers to what is religion or what does a specific religion present to people, and instead flipping it, and thinking, what do people who are devout or religious, what do they do? And what can we learn from the things that they do about what religion is? So it can be about their specific tradition, but also religion as a general concept. My project is really spatially based and anchored in one place, at least this project is.

I settled on processes of craft and construction and building because of the material and religious landscape of this one city in Northern Thailand, where I've spent a lot of time, Chiang Rai, where one of the main things that Buddhist people do is build, they build temples, they make Buddha images, they renovate things. So the project, which comes out of my dissertation and my fieldwork, grew from that, from being in the place and seeing what people did and then realizing, well, this is a really rich ore to mine ideas of religion more broadly.

Annette (05:29):

Yeah. Good. So let's just stay with that for a little bit and think about this idea of religious construction, of making, as being both a making of physical spaces — so we're talking about actually creating temples, using materials to make the buildings within which worship happens – we’re making the physical space in which soul work is actually done. So it seems that there are two kinds of labor: there's the physical labor with the hands, which then imprints itself onto the ethical and religious identity of the individual or perhaps of the community undertaking that work. Adin, could you say something about this?

Adin (06:14):

Sure. as I'm thinking through these ideas, I've been really influenced by some recent work on micropolitics in new materialism and that body of theory that comes out of it. And the way I understand new materialist treatments of micropolitics is, I understand it in terms of the bodily disciplines and practices that give rise to feelings or experience that enable ethical action in some way. So it's very much about this sort of material experience and practice. And I think this is something that medieval thinkers are really preoccupied with. So the closest example I can think of in my period and in the literature that I examine is Piers Plowman, which is a weird and wonderful dream vision by William Langland, who's a contemporary of Chaucer. And the central focus of this narrative, which of course goes all over the place—from the waking world into dreams, into dreams within dreams and all sorts of strange frameworks like that. But through this whole narrative the narrator, the dreamer, is focused on, first he's seeking Truth. And then the search for Truth shifts to a search for Do Well, which is this sort of personification of ethical action. And then from Do Well into a search for Charity, which is both the feeling of love that enables ethical action and the action itself. And what's really interesting to me is that Langland or the dreamer at the beginning of the poem asks for a craft by which he can understand, he can come to have this what he calls, “kind” knowing, or “kynde” knowing, this sort of natural knowledge of Truth, Do Well, Charity. And so there's this sense that craft can —some sort of craft, some sort of habits, some sort of material practice —can inform this internal search that's taking place.

And I'm interested in thinking about that in relation to, I mean, Langland has a lot to say about actual craftspeople and the commodification of craft in late medieval England, and the sort of institutionalization of craft and thinking of a passage in which the personification of covetousness is actually a weaver who has a weaving workshop. And he teaches his apprentices how to pull the cloth so that you can use less material but stretch it out so that it's a lower quality cloth basically. But it will go farther. So this is an in-ethical practice and that really calls attention to the need for governance of craft as an industry, various crafts as an industry. That's just one example.

Music (9:28)

Annette (09:35):

That's fascinating. And it gets to the link between perhaps craft and craftiness and honest craft and, you know, the craft of lies, which of course is the other meaning of fabrication.

Adin (09:49):

Those two are so connected. But then there's the other side of craft in terms of lies as craft in terms of playfulness and positive fabrication or fabulation in some way as well, which is also… all of these things are important.

Annette (10:07):

And we can talk about that in a moment, perhaps in relation to your work with language, because of course playing with language has to do with that sort of seeing of double possibilities. Anthony, do you want to add from your perspective?

Anthony (10:20):

Sure, especially this question, what you called “soul work” which Adin defined as through Piers Plowman, this quest first for truth or access to truth, I guess, and then an ethical desire for doing well. The search for a material practice that can lead one to these ethical modes of being or access to that truth or knowledge of that truth. In the Buddhist case, in the Theravada Buddhist case, we wouldn't call this soul work. They would call it non-soul work, I guess, because they don't believe in a soul. But the notion that's put out from that term “soul work” is really well theorized and established in Thai Buddhism. It's something they would call boon, which means merit, sort of spiritual currency. And the word that they use is Tamboon, literally to make, or to do what is meritorious. It can also mean to generate merit as a substance through good action. There's a lot that can be said about boon, but in my work specifically, it's how engaging in ethical and community-oriented, Buddhist-oriented forms of material and spatial production generates this thing called boon and also other good qualities. And what has become very evident through my work with villagers, monks, craftspeople, administrators, people raising money for the construction of Buddhist temples and diving into the corpus of vernacular and canonical texts that deal with modes of building and religious material production, is that it’s not just that engaging in this material practice or this embodied practice informs things like social, ethical, political good, but indeed is the way that those things are generated.

So through doing these good things, through making merit or generating merit, people are producing their social landscape of other good people that they hang out with, that they do these good things with. They're also articulating what is right and wrong. And I think that's a big part of what focusing on crafting and material production can show us as people who observe or analyze the world, is the way people talk about the built environment, how it's built, who builds it, why things are built, are really articulating their ideas of what's good and bad, what's right and wrong, how the world should look and how it shouldn't, how people should behave within it. And not. So much of that is freighted onto discourse about the material world.

Music (13:20)

Adin (13:29):

I just thought this could be a good moment to observe something that came up during your presentation, Anthony, which is your care with words and your care with language; language as one of the material practices and the material habits that contribute to the ethical work that we're both talking about.

And I was just fascinated by the ways that this term Barami in Thai encompassed a range of concepts in English from charisma, which is what it's often associated with, but also luck or maybe something like what people in the Anglo Catholic Protestant tradition would call Grace or Providence. And then also skill, like craftsman skill or talent, but then also neighborly love of some sort. So all of this really vast semantic spread that fascinatingly collocates all of these ideas about material making, immaterial presence. So I think I was just wondering about how you consider language or words in your methodology and in your approach. And maybe give us another example or two of key terms in Thai that figure into your work on fabrication, and / or put pressure on Western notions around fabrication.

Anthony (15:01):

Sure. Yeah. I mean, you bring up Barami, which is a little bit similar to boon in that it's something that's generated through… Well, it's generated through a lot of things, but it's a spiritual quality. The poly term would mean something like perfection. And then, just like any word, as it travels and traveled through Thailand, it gets deployed in different ways. It can also change to mean totally different things. Or people can use it one way more so than another way. And I think in terms of methodology, being careful with language, first of all, it comes out of the history of Asian studies and Orientalism, and trying not to interject my own conceptions of the world into what people are saying, or what's written down and instead take the terms, indigenous terms, and learn from them what they can tell us about the world.

Music (15:56)

Anthony (16:05):

If I go to a Buddhist temple and people start talking about Barami, and I'm thinking about it in the poly scriptural sense, I'm not going to understand what they're talking about because they're using it in ways that aren't present in that canonical existence, and a man, Charlie Hallisey writes about this. So instead it takes a lot of hanging out, listening, spending time with people, being open to how they're using these terms to really figure it out. So if I just stick on Barami, there's a sort of little couplet people will say in Thai, which is “sang wat, sang Barami”, which means building a Buddhist temple builds Barami. “Sang” is the Thai word for “to build.” When I would hear this over and over again, and people would say this if I’d asked a question about Barami, or I’d asked a question about ‘Why is building temples important?’ – one of the stupid questions I would ask when I would go do ethnography, and people would say that, it's like a big neon flashing sign, like; okay Barami is really important. You have to understand what this means within that couplet within that context and to this person who's saying it.

Being careful with language comes from, okay, the time it takes to study and learn Thai, but also the ethnographic experience of being with people and asking them questions, and then them giving you answers. And instead of sitting around, waiting for what I want them to tell me, actually hearing what they're saying.

Annette (17:37):

Can I jump in and just turn the same question back to you, Adin? You're working in Middle English. You're working with a language which is ours and yet not ours, it's close and yet it's distant. And you don't have a subject who you can go to and say, “what does sliding mean here?” Or, “what is the valence of these particular terms?” And you've spoken a little bit about what you see as the capaciousness of some of the Middle English language that you're working with, a sort of semantic openness or richness that perhaps has been lost to modern English. Would you say a little bit more about that and how you deal with that as a scholar, how you approach that business of language which is and isn't familiar?

Adin (18:27):

Sure. Yeah. Very similar issues are at stake in what I'm doing as well—although as you point out, Annette, I don't have people that I can ask to clarify about terms. Methodologically, it's still about sort of figuring out how the term is used in its context and sort of taking the logic of the text and, sometimes not just one text, but multiple texts and multiple usages, and trying to figure out the nuances of the term. A lot of Middle English words have broader semantic ranges than their modern counterparts. Sometimes they also have narrower semantic ranges as well, but I'm particularly interested and excited about when there are broader semantic ranges. So the word I mentioned earlier ‘kynde’ is related to our word ‘kind’. But in Middle English it has this range of meanings from generosity, but also naturalness. So kindness, generosity, naturalness, and also sort of place within a taxonomy. So that's just an example of a kind of semantic richness of Middle English.

Anthony (19:48):

Adin, I see your methodology in how you approach language really playing out in your amplification of the medieval definitions of ‘creatureliness’—especially in how you are connecting it to contemporary theory, and using it to understand and nuance current conversations in eco-criticism. Could you talk more about how you do this?

Adin (20:14):

Yeah. I think you're exactly right about the ways that I'm trying to turn to medieval terms and place them in conversation with contemporary theories. So, for example, there's a lot of discussion of the sublime in contemporary theories of aesthetics and eco criticism and new materialism. I'm really interested in this and interested in the experience of sort of self-obliteration that's associated with the sublime, but then also self-reinforcement that comes after the sublime. But I've sort of wondered, well, what is the medieval precursor of the sublime? That has led me to the idea of wonder and the condition and experience of wonder. Similarly, as you point out Anthony, this turn to the creature is also a turn informed by my readings in new materialism, contemporary theories of the human and human relationship to animals which has been really oriented toward troubling the relationship between creator and created thing, between the subject and the object of creation.

Music (21:30)

Annette (21:36):

That question of the relationship between creator and created thing, it makes me think about the way that making and crafting itself is theorized in religious studies as achieving a mediation between the divine and the human. And we read about this in your work, Anthony.

Anthony (21:55):

Yeah, I mean, this is really articulated by a scholar Birgit Meyer, who is a professor at Utrecht University. And she has a whole theory about mediation, which is through creating religious objects, religious spaces, the distance between the divine and the human is mediated and shortened, right? So that act of production is condensing distance, compressing distance. So through material objects, materiality, humans are able to access certain divine powers, right. Birgit Meyer works on Christianity in Africa but she writes more broadly than that. And so with my work, I've introduced the Thai Buddhist case where a lot of times what's happening is when people are working on building Buddhist temples, making Buddha images, things like that, actually the gods come and help. So the gods are also involved in the work. It's not that the humans make this thing so that then they can access the gods, like the tower of Babel. It's like if God went and helped with the tower of Babel, or if angels came down and helped with the tower of Babel.

And so this is why I really focus on construction as a religious process in a religious activity, in and of itself, because in the Thai Buddhist case, God's angels, what you would call angels, humans, monks, they all work together on these projects. And what's being mediated a lot of times has to do with people's conceptions of their rebirths over very long periods of time. So they're very often accessing things that happened in the past, places that were significant in the stories of the Buddha traveling around. And a lot of times angels and gods are present as a given, not as the end goal. I mean, this gets back to that question of what does material production afford people? What does it allow them to do? So I wonder in your work, Adin, in the medieval context, what are you seeing? How is it presented as allowing people to do certain things?

Adin (24:10):

So I am going to return to the concept of soul work, I guess. The first thing I have in mind and the thing that I'm most compelled by at the moment is the idea that material work on the self and material work on both the body and one's individual sort of experiences and feelings allows one to do almost everything, I guess. So it cultivates compassion; it cultivates charity, in the sense of feeling and also sort of acting on that feeling. And so, it really facilitates a way of relating to others in the world that is much bigger than just the individualized concept of identity that is implied in the idea of care of the self.

The medieval idea of self-care taps into this much larger ethics of social relation, and web of social relation. I think I'll leave it at that for the moment.

Annette (25:23):

Good. So your work is rooted in disciplines apparently worlds apart, from 14th-century England to 21st-century Northern Thailand, from alchemists, philosophers and the creation of poetic language to Buddhist craftspeople and the construction of sacred buildings.

Anthony, you talked a little bit about Birgit Meyer as, as somebody whose work could speak in interesting ways to the kinds of questions that Adin is asking. Adin, can you think of something that might open up worlds for Anthony, that don't necessarily cross the path of a religious studies scholar working in Thai Buddhism?

Adin (26:05):

Sure. So, I mean, the first thing that comes to mind, I would really encourage you to think with me along with this idea of micropolitics and the ways that making and practices and habits create the interior feeling that conditions action or inaction in the world. And I know that we've talked about Jane Bennett. And so I know you've read Jane Bennett, Jane Bennett is one of the people who mentions micropolitics. There’s another scholar, William Connelly, who's also talked about micropolitics.

He's been talking about a Deleuzian idea of belief in the world, which preconditions and enables social relationships. So he writes “the term belief functions on more than one register. There are epistemic beliefs, some of which can be altered relatively easily by recourse to new evidence and argument. And there are more intense, vague existential dispositions in which creed and affect mixed together below the ready reach of change by reflective considerations alone. This is the zone that prophets tap. It is the one the media engages too through the interplay of rhythm, image, music and sound. ‘Belief’ at this level touches for instance, the tightening of the gut, coldness of the skin, contraction of the pupils, and hunching of the back, that occur when a judgment or faith in which you are deeply invested is contested, ridiculed, ruled, illegal or punished more severely yet. It also touches those feelings of abundance and joy that emerge whenever we sense the surplus of life over the structure of our identities. That is the surplus Deleuze seeks to mobilize and to attach to positive political movements that embrace minoritization in the world.” I think I'll stop there, but I'm really interested in that description of the sort of physiology of belief and the ways that it enables one to act, or not act, as the case may be. Yeah, so there's a kind of spirituality to it. There's a spirituality to the politics of it in ways that I think overlap in our work.

Anthony (28:30):

Yeah, that's excellent. I can think of so many examples that I won't go through. What that makes me jump to is that physiology of belief is itself done in collaboration with the material world and the geography and landscape in which one lives, spends time, and the things that are encountered. And that maybe brings it to that idea of the cyborg, right? That our physiology is itself connected with the tools that we use and the way that we interact with the world. So I will definitely check that out. It brings up so much for me in my work, in terms of, well, first of all, the word “belief” is used by Thai Buddhists for things that are not exactly canonically recognized Buddhist ideas. When I would go somewhere and start asking people questions, in Buddhist temples, when I would ask people questions about rebirth and temple building, and I would say, okay, well, I've heard that people believe when they're rebuilding an old temple, temple ruins, they're rebuilding a place that they had built in a former life.

People would say, “Oh, well, that's a belief.” They say, “Oh, man ben khwam chua” they'd say, “that's belief,” emphasizing belief to differentiate it from what they would consider to be Buddhist teachings, Dharma, right. Because the problem with, when you go to a Buddhist temple and tell people that you're a PhD student, or you're writing about Buddhism, they say, “well go talk to the monks.” Or like, “I don't know anything about that.” ‘Cause they think I was looking for Buddhist teachings written in the texts. And so once they understood I was actually talking to them about these things that they call “khwam chua,” belief, that opens up all these different possibilities of exactly what you're talking about. Maybe micropolitics is a word for it, right. But it's how they're engaging, physically engaging with the world around them. And it's informed with Buddhist concepts, but then also things like: they're working in their fields and they find a Buddha image when they bend over to pick it up. And then they have some sort of experience that generates into belief.

Music (30:48)

Annette (30:58):

I wonder if we could turn to talk a little bit for a moment about the senses, which I know figure into both of yours work. Anthony, you've written about touch and thought a lot about touch, the hand of the maker in the process of making. Adin, likewise, you've written about sound. And I wonder if we could just talk a little bit about the senses and perhaps the specificity of materials and how materials work in the work that you do.

Adin (31:35):

Sure, yeah. In a very basic sense, what unites my first book on sound and noise with my current project is thinking about the materiality and embodied experience of language and reading. So in my first book, I was interested in the ways that language could be experienced as noise with an emphasis on sounds and feelings as much or more than semantic content. And I wanted to really call attention to the ways that medieval thinkers had anxieties about that, but also emphasized the importance of the sounds and feelings of language. And I think that is coming through in this next project as well as I think about human relationships to technology and sort of embodied relationships to technology and the ways that language as a technology can affect and change human embodiment and consciousness in various ways.

I’ve just been working on an article on Julian of Norwich that discusses what scholars have called her “word knots,” which are these collocations of punning or chiming words like “fail,” “fall,” and “feel” in passages that, I mean, my experience of these passages is that you read them for the content, but you notice there's a materiality to them in the ways, in these time chimes and overlapping textures and sounds of these words, and I can best describe this in terms of the process of reading. It slows one down and it sort of opens up all of these various interpretive possibilities in ways that really enrich an understanding of the material. And Julian of Norwich has so many of those. I'm thinking of knotting and knitting and knots - so N O U G H T, K N O T, and so many of them. Anyway, so it’s a really interesting approach.

Annette (34:02):

Would it be fair to say that it's as much about reading out loud as simply reading—that it's about hearing and working the sounds both in the ear and in the mouth?

One has the sense that there's a kind of “mouth feel” to the way that this language is working, which demands that you take time over it?

Adin (34:23):

Yes. Yeah. I think that's right. I certainly think that reading aloud helps all of this, but I think the issue was time. And I'm, and this, again, I mean, this makes me think of the ways we've been talking about care and attention and scholarly labors as a type of care and attention. I certainly think that reading aloud is a good way to slow down and make this kind of experience happen. But I think just reading slowly, which one kind of has to do with Middle English anyway, is, it's possible to attend to them and to attune to them in various ways.

Anthony (35:04):

I want to bridge that Adin, to something you brought up earlier before we started recording which is humor and the focus on humor. Because I think that's somewhere where both of our works overlap. We haven't talked about it yet, but I think we're both slowed-down readers. Not slow readers, but readers who slow down because of the texture of the languages that we work in, and when you start paying attention then, it's a hermeneutic puzzle, but where's the humor, right? It's in the text, but also it's in the reader who sees it. I want to hear more about your approach to humor, when you find things that are funny in your texts, and then how you use humor as an expression of your scholarly care, how drawing out humor is a form of scholarly care. Maybe it's not, maybe those are bad questions.

Adin (35:59):

No, I love that question. I mean, I was going to ask you the same thing just because so much of your work has these really funny moments and funny examples taken from Thai lore and Chronicles that you've been looking at. So I loved the small bear creature with the extra ears and eyes that eats red hot coals and excretes gold in ways that can be beneficial to farmers. Or the King and Prince who points with a finger and causes a bunch of people to fall off their elephants. It's very slapstick and funny. But in your discussion you were so adamant about, well, I don't think you were over adamant, but you sort of raised the issue of “Do I just think this is funny because it's different and strange, or is there a kind of intentionality to the humor here?”

And I think that is a question that's always at issue with the humor of medieval texts as well. And there is this whole tradition of holy foolishness in the Middle Ages and spiritual mirth or spiritual sporting or jokes “jocunditas” that helps to justify the idea of the humor serving some sort of purpose and doing an important kind of work. Drawing attention to humor is connected to the idea of scholarly care, because for me, part of the care of scholarship is to come from a place of appreciation and love for the material that you're working on and sort of to try to transmit that in some way, or to make it available and accessible to others. I think that's how I understand part of my role as a teacher, but also as a scholar.

Annette (37:55):

I think also jokes and humor are fascinating in the way that they are necessarily collaborative. As you say, perhaps, this is what you mean by care. One has to come to the maker of the joke and be willing to get the joke, to be willing to interpret creatively. So they're collaborative, they're creative. They're often critical as well. And humor injects this kind of personal register in which the maker of the joke and the getter of the joke are put into a kind of contract too, which I think is always a moment in a text that sort of pops out and becomes a place where that responsibility is required too. You need to be responsible if you're going to understand the humor and get the joke.

Anthony (38:39):

Yeah. I love that. And I agree. Drawing out the humor or presenting the humor in a text, it's allowing the text to live as it is, and not having to reduce those things to, “oh, well, this is a political move,” or “it's humorous because these people don't have access to this, that, or the other thing,” but that the humor embedded in these texts is part of its sensual appeal but that sensual appeal of the text, a lot of times, is a big part of why the text is important or why it stuck around. So this can be done with humor. I think, I mean, there's another example from the larger story of the bear-like creature that eats hot coals and excretes golden nuggets, the Maeng Sihuhata who is one of my favorite beings ever, but there's a temple building project that happens in that text.

And there's a long, probably page and a half, list of all of the different types of food that was cooked by the people who were building this temple. And it goes on for a really long time. And it's not funny, but when you read it, you read all of these different dishes and all the things that they're made out of, and you start to salivate, your mouth waters.

Music (39:53)

Annette (40:03):

As we draw to a close here, can I ask you both a final question, very straightforwardly. And that would be to ask you if you have something that you could recommend that we should read. It doesn't necessarily have to be related to your current project or to the questions that we've been talking about here, but what's something, Adin, that you think you'd like to suggest that your listeners or your students or your friends should be reading today?

Adin (40:35):

I love this question because I find that reading things outside of my scholarly activity can really do wonderful things for my scholarly creativity and activity as well. So I would like to suggest work by Leonora Carrington. She's a surrealist painter and writer. She's kind of having a moment right now because the New York Review of Books Classics series has re-published a couple of her novels. They just republished The Hearing Trumpet and they published her autobiographical account Down Below. I just think she's a fascinating person. She grew up in a wealthy British family, but had a long-term fascination with Celtic myth and magic acquired from her maternal grandmother. And that kind of eventually made its way along with, or interwoven with, other types of arcane lore into her writing and painting in her later years and her own surrealist mythology there.

She was really deeply suspicious of institutional authority. And she writes about, I mean, just these bizarre absurdist tales and stories of humans interacting with animals; animals, taking the place of humans, vegetables, fighting with each other and fighting with humans. And so it's these really wonderful stories of an animate universe, I would say. I'm also really interested in the ways that she conceptualizes below-ness or deepness in her work. She's thinking it through in relation to the unconscious and the body and hell or the underworld. I think she has a lot to say; she can really sort of speak to our moment. And I'm not the only person saying that; there are articles in The New Yorker and The Baffler, this is part of her sort of re-emergence these days. She writes about very contemporary things. So her novel The Hearing Trumpet is essentially about climate catastrophe, but she does it in a way that's so full of wry humor, and joy, but also a serious sense of responsibility to other creatures that I think is just wonderful to read. And it sort of gets at the spirit of what I'm going for with this project.

Annette (43:11):

Wonderful, and full of wonder…

Anthony, do you have a suggestion for us?

Anthony (43:17):

Sure. It's a book that came out a couple of years ago, but I'm still thinking about it and thinking with it. It's Daegan Miller's This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent. First of all, it's one of the most elegantly written academic books I've ever read. It's so well sculpted and crafted. It takes the reader sort from East to West, across the continent of the contiguous United States through history and explores different communities of people or individuals who settled with radical politics or progressive ideas of freedom and exuberance. It inspires me to go back to things that I've read or notes that I've taken and rethink the importance of landscape for communities, for people, the political ideas, how they organize themselves. And what's important to them. It's just an excellent book. And I think as many people should read it as possible and I've been giving it to a lot of people and I still am, even though it's a few years old. So Daegan Miller's This Radical Land.

Annette (44:28):

Thank you. This has been great. Thank you both very much indeed, Adin Lears and Anthony Lovenheim Irwin, for taking the time today and talking to us on the Humanities Pod.

Adin (44:41):

Thank you.

Anthony (44:42):

Thank you, Annette.

Annette (44:43):

We've been talking today with Anthony Lovenheim Irwin, scholar of Asian religions, and Adin Lears, assistant professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University, both fellows this year at the . The Humanities Pod is a production of the , introducing you to some of the new work, the current conversations, and the latest ideas of humanists at and around Cornell. The Pod is produced by Tyler Lurie-Spicer. Our music is from The Continuing Story of Counterpoint by David Borden, performed and recorded by Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Company. Our thanks go to the College of Arts and Sciences, and the Cayuga Nation, on whose traditional lands Cornell is situated.